Rabbit Bullet

Algorithm

2020

Algorithm is an installation of minimalist readymade sculptures accompanied by a catalogue of found digital images, procured per the suggestion of digital advertisements that appeared in my social media feed. The installation is a study of form and abstraction, which takes on symbolic undertones when understood through a feminist, post-consumerist lens.

Select works + full artwork statement below.

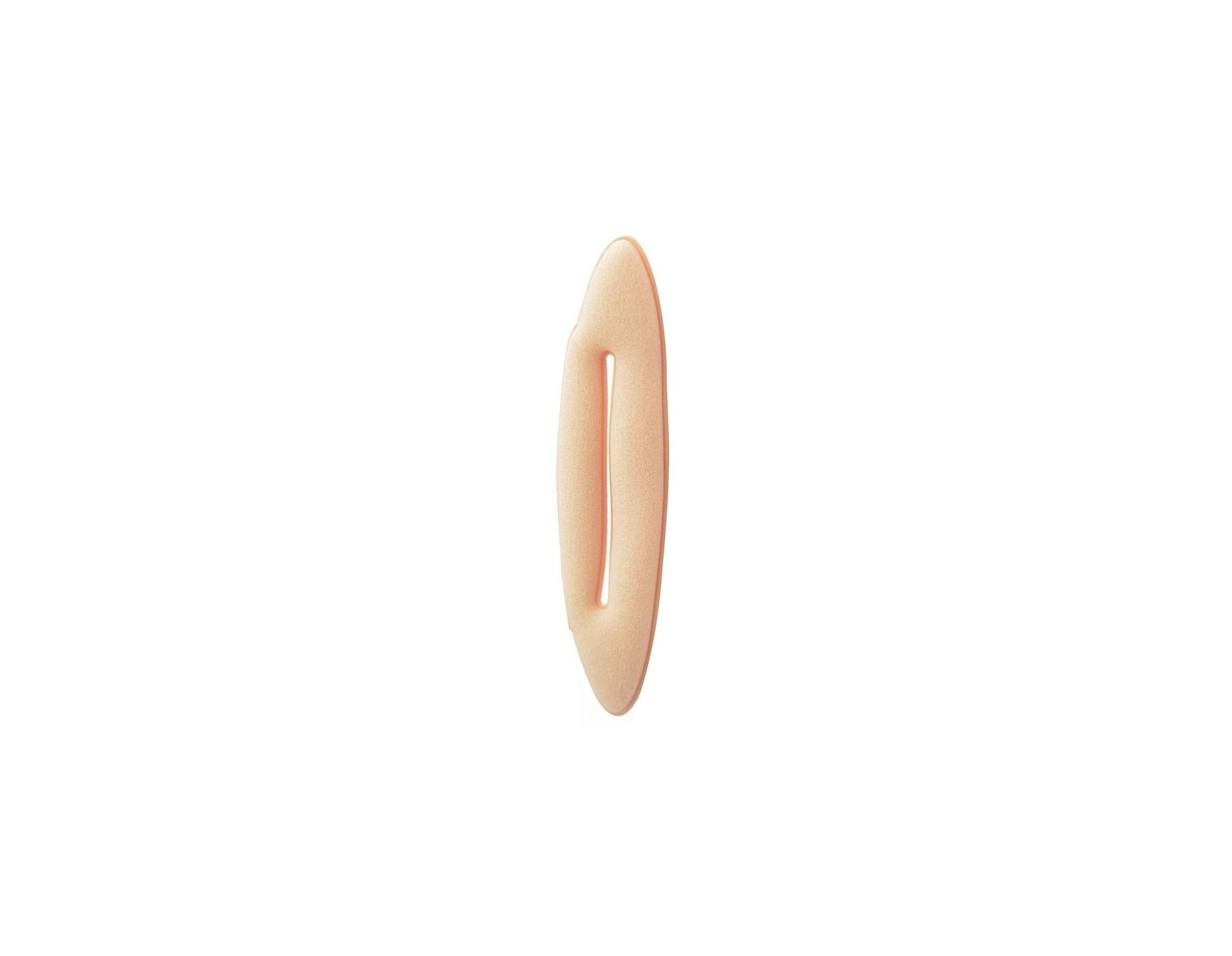

Insert (Half Up)

Don’t Look at Me

Tension (Relief)

Rack (Mommy Juice)

Brown Cave

Protect (Repel)

Nearly Natural

Mount

Algorithm is an installation of minimalist readymade sculptures accompanied by a catalogue of found digital images, produced per the suggestion of digital advertisements that appeared in my social media feed. In 2018, I began living an eco-minimalist lifestyle, consuming as few new products as necessary. In the process of going zero-waste, I went through a stage of unfollowing shops on social media and unsubscribing from promotional emails. I even took to hiding every single ad I came across in my Instagram feed, selecting “It’s not relevant” as the reason I didn’t want to see the ad.

•••

Hide Ad

It’s not relevant

•••

Hide Ad

It’s not relevant

•••

Hide Ad

It’s not relevant

•••

Hide Ad

It’s not relevant

In doing this, the algorithm recalibrated and, as a result, the ads became increasingly strange. I imagined that the code was asking itself, “Okay… so what does this woman want to buy then?” Advertisements shifted from makeup, clothing, interior decor, and home improvement items (products which had been targeted to me based on my demographics and my past purchasing and “liking” behaviors) to items that were tangentially related to those same categories but whose intended uses were entirely elusive at first glance. Ads still came to me from West Elm, Bed Bath & Beyond, Wayfair, and Overstock, but the products were more unusual. And when photographed against a white background and placed entirely out of context in my social media feed, the items became quite sculptural.

Some were formally intriguing, some were strangely visually satisfying, and some seemed simply absurd. Many were all three. Sometimes the description told me what the item was. Often times, there was no telling what the item was. In those cases, I was almost always intrigued enough to actually click on the ad—not because I wanted to buy the product but because I needed to know what the product was. I began collecting screenshots of these bizarre product ads and, over time, the amassing collection that began as an interest in form and abstraction took on new meanings. Symbolic undertones developed as I looked at them through a feminist, post-consumerist lens.

The titles employ tongue-in-cheek humor and double entendre often derived from the nature of the item itself or its product name. A few of the products, when seen out of context, took on references of the body, some of which seemed overtly gendered or sexual to me. Others became gendered or sexualized as I began to learn more about what they were. For example, an ad image drew my attention to a shiny phallic object whose use was not immediately apparent. This time, the caption told me what the object was: Rabbit Bullet Cocktail Shaker. Right away, the product name intrigued even further, as “Rabbit” and “Bullet” are both popular styles of vibrators used for clitoral stimulation.

Rack (Mommy Juice) refers to a sculptural object that for me, as a city dweller with virtually no connection to rural life, looked like some sort of torture device. Again, its use was unrecognizable to me upon first observation. By clicking on the ad, I was able to learn that the object was a rack that a vintner or dairy farmer would use for drying bottles used for wine (“mommy juice”) or milk (“mommy juice”). And of course, the word “rack,” a euphemism for breasts, befitted the work. Serendipitously, I later came to find out that Marcel Duchamp, “Father of the Readymade” himself, produced a bottle rack sculpture in 1914.

In the interest of seeing if the 3-dimensional objects would read as abstractly in the physical world as their 2-D likenesses had in the digital world (spoiler: some do and some do not), I began purchasing the objects that had been advertised to me. And so in a perverse twist of fate, the code recalibration had proven successful. The algorithm had “won” and Algorithm was born.